From peaty scotch to smooth bourbon, the magic largely happens in those iconic stills. But did you know that the shape of a whisky still plays a pivotal role in the spirit’s final flavor?

The Science Behind the Shape

At the heart of the distillation process, the still is tasked with separating alcohol from the fermented wash. The science here is fairly straightforward: alcohol has a lower boiling point than water. When heated, alcohol vapors rise, get condensed, and are collected as liquid.

However, not all these vapors cut. Only the ‘heart’ – the middle part of the distillation – is used in whisky production. The ‘heads’ and ‘tails’, the first and last parts respectively, are generally discarded or redistilled. And here’s where the shape of the still starts making its mark.

The Pot Belly and the Long Neck

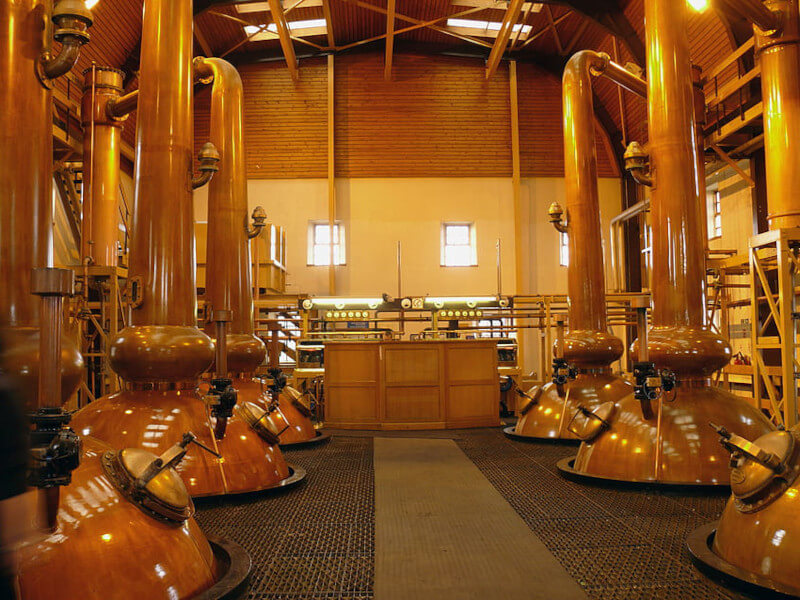

Classic Scottish pot stills often have a broad, round base and a tall, slender neck, that directly influence the spirit’s character. This shape does two main things:

1. Surface Contact: The wide base provides ample surface area for the wash to be in contact with the heat. This ensures an even and consistent distillation.

2. Vapor Path: A tall neck means the alcohol vapors have a longer path to travel, and this affects which vapors reach the top and which don’t. Lighter compounds tend to rise higher and are thus more prevalent in whiskies from tall-necked stills, giving them a lighter flavor profile. The tall, elongated neck aids in refining these compounds. Whiskies produced from such stills often have a light, aromatic profile, replete with floral and citrus notes.

The Impact of Reflux

Reflux is when some of the rising vapors condense before they reach the top and trickle back down into the pot. This process essentially redistills the spirit, making it purer but also affecting its flavor. A study by the University of Edinburgh highlighted how the angle and shape of the line arm in pot stills could modify the reflux rate, again influencing the spirit’s final taste. More angled arms promote more reflux, leading to a spirit that’s lighter and more refined.

Column Stills: Efficiency with a Twist

Column stills, favored in bourbon production, are more efficient than pot stills and can operate continuously. The Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) reported that the use of column stills has risen due to their ability to operate non-stop. They consist of two columns: the analyzer and the rectifier. These stills have multiple plates or trays where reflux happens, leading to a more consistent, albeit less characterful, spirit. The shape and number of these plates play a crucial role in determining the spirit’s final flavor.

While this ensures a uniform spirit, the flavor might lack the robust character found in pot-distilled whiskies. Instead, you’ll find a consistent, cleaner profile.

European Nuances: Cognac to the Rescue

Europe, especially regions like Cognac in France, has a rich distillation history too. Their stills, called alembics, have a distinct onion shape that promotes more reflux than the Scottish pot stills, leading to a different, often fruitier profile in their spirits. For those seeking vibrant, rich flavors with an emphasis on fruit notes, alembics are the go-to.

Copper Contact

As found in a 2017 research paper published in the Journal of the Institute of Brewing, the contact of vapor with copper removes sulfurous compounds, known to impart a ‘meaty’ or ‘rotten’ note. Thus, a still shape that ensures maximum copper contact during distillation will result in a smoother, more pleasant whiskey.

So, Does Shape Matter?

Absolutely! The shape of a still can influence:

The Copper Connection and Sulfur Compounds

Copper, an essential element in the distillation process, plays a pivotal role in refining the spirit’s taste. The Royal Society of Chemistry published a report which highlighted that copper acts as a catalyst in removing sulfurous molecules present in the vapor. Why does this matter? Sulfurous compounds can lend unpleasant, sometimes even ‘rotten’ notes to the whiskey. When vapors come in prolonged contact with copper, especially in a still with a broader surface area, these compounds are effectively neutralized, resulting in a smoother drink.

Speed and Efficiency in Distillation

The shape and size of a still can impact how quickly the distillation process occurs. A study by the Distillation Research Group at the University of Louisville showed that tall, slender stills with elongated necks lead to increased vapor travel times. This extended travel allows for a more refined spirit. On the contrary, broader stills lead to faster distillation but might compromise the complexity of flavors.

Reflux: Filtering the Unwanted

Reflux, a core concept in distillation, is influenced dramatically by the still’s shape. A pointed observation by the American Distilling Institute noted that pot stills with upward-sloping lyne arms lead to enhanced reflux. This means heavier, unwanted compounds get condensed back into the pot. The result? A lighter, refined spirit. In contrast, a downward-sloping lyne arm would reduce reflux, giving a richer, full-bodied spirit.

Crafting the Flavor Profile

Different compounds boil at various temperatures, and the still’s shape determines which of these makes it to the final product. The International Journal of Food Science & Technology carried out an experiment wherein they found that narrow-necked stills, due to the increased surface area, led to a higher concentration of esters (flavor compounds) in the final spirit. This is why spirits distilled in such stills often have pronounced fruity and floral notes.

Each distillery often swears by its still design, believing it to be a key component in crafting its unique spirit. While the shape isn’t the only factor (the ingredients, aging process, and even local climate also play their roles), it’s undeniably a crucial one in the rich tapestry of whisky production.

In the intricate world of whiskey production, the shape of the still undeniably stands as a pivotal factor in determining the spirit’s final flavor. It begins with the interaction with copper and moves through the nuances of reflux, the still’s form has a pronounced hand in refining and defining the whiskey’s character. Distillers, in their quest for perfection, often find that the design of their equipment isn’t just about aesthetics or tradition—it’s an essential tool in the craft of spirit creation.